e - M U S I C L A B THE THEORY

- FRONT END / NEEDS ANALYSIS

- INSTRUCTIONAL GOALS

- THE TECHNOLOGY

- THE INSTRUCTION

TASK ANALYSIS

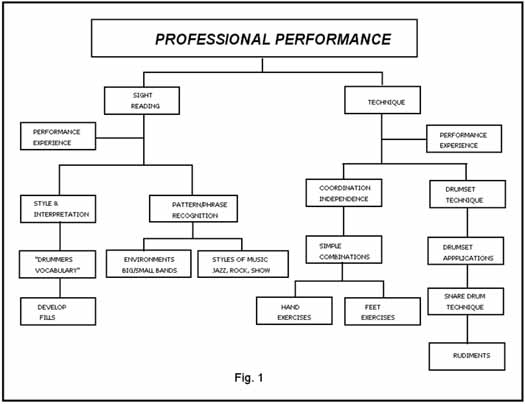

There are several areas to concentrate on in the training of a drumset player. The task analysis in Fig. 1

shows the development of two areas: sightreading and drumset technique.

- TECHNIQUE

SNARE DRUM -- BASIC TECHNIQUES

- READING AND INTERPRETATION

- MOTIVATION

- FORMATIVE EVALUATION

There are many techniques and skills that a musician must master -- how to create a pleasing sound, how to breathe to support the sound, how to play in tune, and how to read music, etc.. Woodwind (clarinet, flute, saxophone, oboe, etc.) and brass (trumpet, trombone, tuba, french horn, etc.) players who learn intricate fingering combinations and slide positions, also develop facial muscles to control their pitch and sound. String (violin, viola, 'cello, and bass viol) learn bowing techniques and complex fingering positions and pressure applications. Pianists learn to see and play two or more staves of music simultaneously. Drummers/percussionists have their own set of basic techniques to master: rudiments for the snare drummer, mallet techniques for the tuned percussion family (vibraphone, xylophone, marimba, chimes, etc.), tuning and etude studies for the timpanist, and the percussion hand instruments (cymbals, triangle, tambourine, etc.) as well. All musicians practice scales and other exercises designed to develop proficiency on their instruments.

It is often the responsibility of the school instrumental instructors to teach ALL the band and orchestra instruments (an overwhelming task). Students who desire to develop their abilities beyond those of basic school instruction often find it difficult to locate a private teacher who can take them beyond the capabilities of their school teacher. In addition, in many locales, it is difficult to find a live music concert to hear and see professional musicians perform.

To meet the needs of student and educator e-MusicLab will develop a set of interactive, World Wide Web lessons on drums, guitar, bass, and keyboards in the near future and ultimately each major band and orchestra instrument. The educators/clinicians who will deliver the instruction in these lessons will come from major symphony orchestras, top universities, and the recording studios of New York and Los Angeles.

These lessons will have application on several levels. Music educators from across the country have responded to a survey concerning the design and applicability of the concept of e-MusicLab. Their responses were illuminating. Without exception, all indicated they would welcome this teaching system into their classrooms. They indicated these lessons would be invaluable for beginning through advanced band and orchestra classes in elementary and secondary schools. It was suggested that university music education majors might use the lessons (in preparation for passing a required barrier examination on each of the instruments). Instrumental instructors are likely to use the lessons during rehearsals. Students musicians would be encouraged to use the lessons for individual research and practice. The music educators were particularly interested in the drumset instructional system as few were drummers themselves and had limited knowledge about the development of a student drummer.

With regard to cost, music education administrators were determined to acquire e-MusicLab no matter what the cost. The cost of the computer setup and e-MusicLab were considerations but not deterrents. The only negative comment came from someone planning to create a similar package.

In order to compete as a professional musician drummers must develop a multitude of skills. In addition to mastering basic snare drum technique (the rudiments), drummers are required to develop facility on the drumset (requiring ambidexterity, coordination, and hand/foot independence), a knowledge of styles (from Dixieland to the most current forms of music), and the ability to sight-read music. I taught graduate and undergraduate drumset students who ranged in ability level from beginner to professional at The University of North Texas from 1972-1974. I realized as I auditioned 75 drummers for the eleven 20-piece jazz lab bands at UNT that, while many had great technique, only a few had the skills to adequately sightread (read a drum part for the first time) and not get lost in the music (or lose the band). The discrepancy between the technical skills and the sightreading abilities of the students clearly defined the gap (Rossett, 1987). To meet the needs of these drummers I developed a program based on my own experiences as a student and utilizing many of the methods I employed. I attempted to create a practicing/learning environment as close as possible to a live playing experience through the study of recorded performances. It was my goal to assist my students in mastering the skills (sightreading, in particular) necessary to compete successfully as a professional musician. It was not difficult to measure students' successes at UNT. After a semester of intense work, some who had never played in a lab band auditioned and were accepted well above the bottom of the pack. Others, already placed in lab bands, practiced diligently and jumped ahead many lab bands. Drummers who were not be convinced that sightreading was important were frequently passed over by newer, more ambitious learners. Former students, who developed these skills, have played with big bands, acts, and shows, and have had successful recording careers. They have often attributed some measure of their success to the study of sightreading and interpretation. With these skills comes a confidence of being able to "do the job" under most circumstances.

The extent of media technology at my disposal in the early 1970's was a self-contained record player and a few well worn records. Using a record for reference meant playing "drop the needle" with less than adequate accuracy and quick destruction of the recording. Live performances by world class musicians were extremely rare and filmed performances were unavailable for viewing in a classroom or teaching studio situation. Practicing with a metronome was boring and unmusical. During a lesson, I spent often much time searching for sheets of music and drum parts, exercises in books, and hunting for music passages on reel-to-reel and cassette tapes. The web-based e-MusicLab will make teaching resources immediately available and video performances of the finest musicians will be available at the click of the mouse. MIDI files, whether short loops or whole compositions, can be played for demonstration or for practicing.

The elementary level of the technique side of the chart starts with snare drum skills which must be

developed prior to studying the drumset. This section of e-MusicLab instructional program will begin

with video excerpts of snare drum solos played by virtuoso drummer Buddy Rich as a demonstration of the

application of snare drum rudiments (the study of which is often considered boring and obsolete by young

drummers).

The rudiments instruction section will detail each of the twenty-six rudiments with the proper performance sticking indicated on individual screens. There will be a MIDI file demonstrating the rudiment being studied (from slow to fast, in the traditional manner) which the student can listen to and play along with for reference. Where appropriate there will be examples of applications of the rudiment along with MIDI files. For further reference (and motivation) there will be video performances of jazz great Dave Weckl, rocker Greg Bissonnette, and studio master Steve Gadd demonstrating their personal rudimental practice routines. The rudiments, once mastered, will then be applied to the complete drumset.

DRUMSET -- COORDINATION/INDEPENDENCE

Much of applying the basic techniques of drumming to the drumset is the development of motor skills. Like "scratching your head and patting your stomach" playing the drumset depends on developing physical coordination and independence of each of the limbs. The hands play the upper part of the set - the snare drum, the toms, the cymbals, etc.,., while the feet play the bass drum and hi-hat pedals. Rock drummers sometimes develop very fast and well-coordinated feet as much of rock music requires involved bass drumming. Jazz drummers develop hand independence as well, as they play around the set improvising with and embellishing the music. It is not unusual for each limb to be playing a unique pattern in direct opposition to what the other limbs are playing, a difficult skill to master and one which must be approached with careful planning.

The instruction in this section will be introduced by a video collage of several jazz drummers demonstrating their independence and coordination abilities. As in the development of procedures, explained in Gagn?'s (1965) theory of motor skills, these lessons will begin with simple exercises combining each limb with another (right hand-left hand, right hand-right foot, right hand-left foot, left hand- left foot). The routines will become more and more complex until eventually all four limbs are playing simultaneously while rhythmically independent of each other.

When practicing, the learner gets feedback in several ways - in a kinesthetic sense when the receptors in the muscles know from the "feel" of the action, by the learner's observation (auditory as well as visual) that the performance was correct or not, and from augmented feedback (or knowledge of results) from a source other than the learner. As always MIDI files will be available for reference (auditory feedback) and to play along with. In addition to the MIDI files with the drumset patterns demonstrated there will be MIDI file loops of music played by a bass player. The student can then practice his new skills in a musical context and begin to develop an understanding of musical formats.

INTRODUCTION -- The introduction in this section will begin with video excerpts from performances by many great big band

jazz and rock drummers including Mel Lewis(Woody Herman, Terry Gibbs), Louis Bellson (Dorsey,

Ellington), Harold Jones (Basie), Peter Erskine (Stan Kenton, Maynard Ferguson, Weather Report), Bobby

Columby (Blood Sweat and Tears), etc.. for reference as well as inspiration. Transcriptions of these

excerpts will be available on the screen.

BASIC READING SKILLS -- It is important that the student drummer develop reading skills. This section of the instruction will address

that issue. Beginning with elementary rhythm patterns the lessons will build in complexity by combining

simple exercises into more complex ones. Each pattern will be notated on a screen and a MIDI file

example will be available for reference.

SIGHTREADING SKILLS -- One of the most important processes to be learned while using e-MusicLab is sightreading - the skill of

being able to play difficult music at first-sight with few, if any mistakes. This skill is particularly important to

the professional who is allowed few mistakes in a recording situation where time is money or in a live

situation where a mistake cannot be fixed. A way to do this is to develop a "drummers vocabulary" for the

rhythmic patterns most often used by arrangers. The instruction process, which I developed at UNT, is

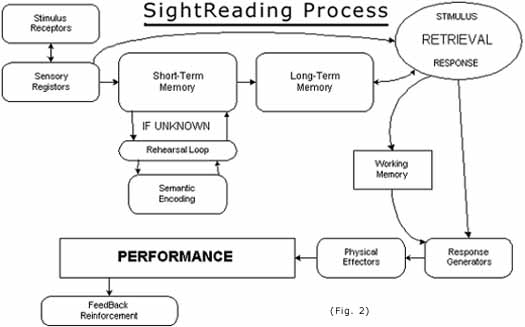

outlined in Fig. 2 below.

This process follows very closely the Short-Term Memory - Long-Term Memory process outlined in Gagn?, Briggs, & Wager (1988). As the drummer sees a new rhythmic pattern in the music, stimulus receptors (the eyes) and sensory registers in the central nervous system turn it into recognizable figures (i.e., music notes). If the pattern of notes is one familiar to the drummer then it moves from short term memory into long term memory from which it can be retrieved and performed. The student with few reading skills will not recognize the pattern and will not be able to play it.

The process employed by the sightreading instruction in e-MusicLab focuses on the rehearsal loop in Fig.2. The student is shown a new pattern on the screen and is given time to decipher it at their own pace. (There will be a MIDI file demonstrating the correct interpretation of the figure available for the student to refer to.) The student will then be asked to rehearse the figure over and over in the context of a short four to eight measure phrase MIDI practice loop which repeats until clicked off. The student is encouraged to continue to keep their eyes on the screen even after committing the pattern to short-term memory so that the pattern becomes solidly fixed in long-term memory. When this occurs the student will instantly recognize the figure the next time they see it in a piece of music and not have to "count it out" it while playing. Rather, they will be able to play a well-rehearsed pattern (response) for the figure (stimulus). As the student progresses, patterns are combined into longer and more complex phrases. With sufficient practice the student drummer will develop their "drummer's vocabulary" of patterns and phrases (stored in long-term memory) that they will be able to call-up play without hesitation.

APPLICATION -- In addition to being able to play a rhythmic pattern or figure "at sight" the drummer is often required to "fill- in" around or embellish the pattern. In order to facilitate the development of these skills the instruction will be presented in the context of a playing situation. Even the simple patterns will be incorporated into MIDI files which will emulate the experience of playing with a band. These files will be created without a "drummer" - the student will add the drum parts. Different styles (and therefore interpretations) of music will be presented and explored - big and small group jazz, rock, fusion, show music (variety TV, Broadway) - all have special requirements. As each is discussed excerpts will be offered on video and on CD-ROM audio, and screens with the drum parts written out will be provided. MIDI files of entire arrangements from the libraries of Stan Kenton, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Woody Herman, Don Ellis, Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, Chicago, Blood Sweat and Tears, Tower of Power, Miles Davis, Frank Zappa, Cole Porter, etc.. will be developed to create the experience of actually playing in each of these bands.

ARCS - e-MusicLab is designed to address the issues outlined by John Keller's ARCS theory (Gagne, R.M. & Perkins-Driscoll, M., 1988):

Attention - arousing and sustaining curiosity and interest

Relevance - learning has personal value or importance

Confidence - learners believe in their ability to achieve goals successfully

Satisfaction - successful completion / reinforcement - feedback on performance

| EVENTS OF INSTRUCTION | ACTIVITIES TO IMPLEMENT THE EVENT | EVENTS | MOTIVATIONAL FEATURES TO ENHANCE APPEAL |

| Gaining Attention | Show learners video clips of famous drummers playing with great bands | Inquiry Arousal | Drummers are playing the same music that learner is studying |

| Informing the learner of the objective | Show drum part and play music from CD. To do this 'at sight' is the challenge | Goal orientation | Inform learner that sight-reading skills enhance pro status |

| Stimulating recall of prerequisite learning | Demonstrate that sight-reading skills are derived from previously learned skills | Familiarity | Sight-reading developed from earlier developed skills |

| Presenting the stimulus material | Describe the method used to develop reading skills - link to current music challenges | Motive Matching | Use examples of music learner is currently learning to play |

| Provide learning guidance | Show how mastery of the beginning lesson carries through to the ending lesson | Expectancy for success | Early accomplishments carry through to the end |

| Eliciting the performance | using the MIDI files, have the learner 'be the drummer' and apply the new skills | Setting Challenges | Introduce challenging tasks as advancements are realized |

| Providing the feedback | Play the MIDI files with the drum parts or the actual recording as a reference for the learner | Positive consequences | Feedback should re-enforce sense of achievement |

| Assessing the performance | The instructor (or learner) can compare the recorded exercises with the reference versions | Equitable standards | The new challenges are similar to previous ones |

| Enhancing retention and transfer | Give addition like exercises for study . . . give same examples in different musical context | Natural Consequences | Discuss different applications for the newly learned skills |

The ATTENTION of the learner is quickly captured through the use of video clips of famous drummers

(see Fig. 4). By using these and other appropriate videos curiosity and interest will be sustained

throughout.

RELEVANCE of the approach will be established with the discussion of the applications of the skills to be

learned and how they are applied to a wide variety of scenarios.

The learner's CONFIDENCE will be quickly reinforced when they are informed of the major objectives of

e-MusicLab - drumset technique and sightreading skills. It will be clearly demonstrated that these new skills

will be developed from abilities already mastered.

SATISFACTION will be optimized by feedback provided from the program (recorded performances) as

well as from the instructor. The learner will be shown how what they have developed can be generalized to

"real world" contexts.

In some ways e-MusicLab will be easy to evaluate...Did the learner become a better drummer? Were they more successful in the lab band auditions? Did they get the job? More importantly, did they KEEP the job? They learner should be able to communicate whether they believe they have developed as a player, while in actuality, their performance level will be the proof. Groups of learners will be queried as well. What did each think of the other's improvement? What about their own (in front of the others)? What did they think of the instructional platform? Did the learners feel motivated throughout the learning process? What about the relevance of the material? Was it too easy/difficult? Where they challenged? Did they receive sufficient feedback from the program as well as the instructor? Ask those who didn't feel they made much improvement 'why ?'. Was some instruction more clearly defined, presented in a more meaningful manner? Was this instructional system more of an "entertainment" than a teaching platform? What about band leaders' (experts not connected with the instruction) opinions of the improvement made by the learners?